When I booked my trip to Tokyo, I knew I wanted to spend a day learning about a local delicacy. While I had considered traveling to a sake brewery, a soy sauce factory and a wisteria park, the moment I saw this wasabi harvesting experience I knew that was the ticket. I had the pleasure of traveling to this wasabi da (field) this past Sunday in Okutama, Japan and being taught the ins and outs of this condiment by David Hulme.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Located 2.5 hours by train outside of Tokyo, the town of Okutama is known for its wasabi. As you’ll read more about below, wasabi grows in water which provides nutrients for the wasabi which ends up affecting the root’s flavor. The water in the Okutama mountains has the perfect balance of minerals for wasabi which imparts an ideal flavor, the golden standard of wasabi.

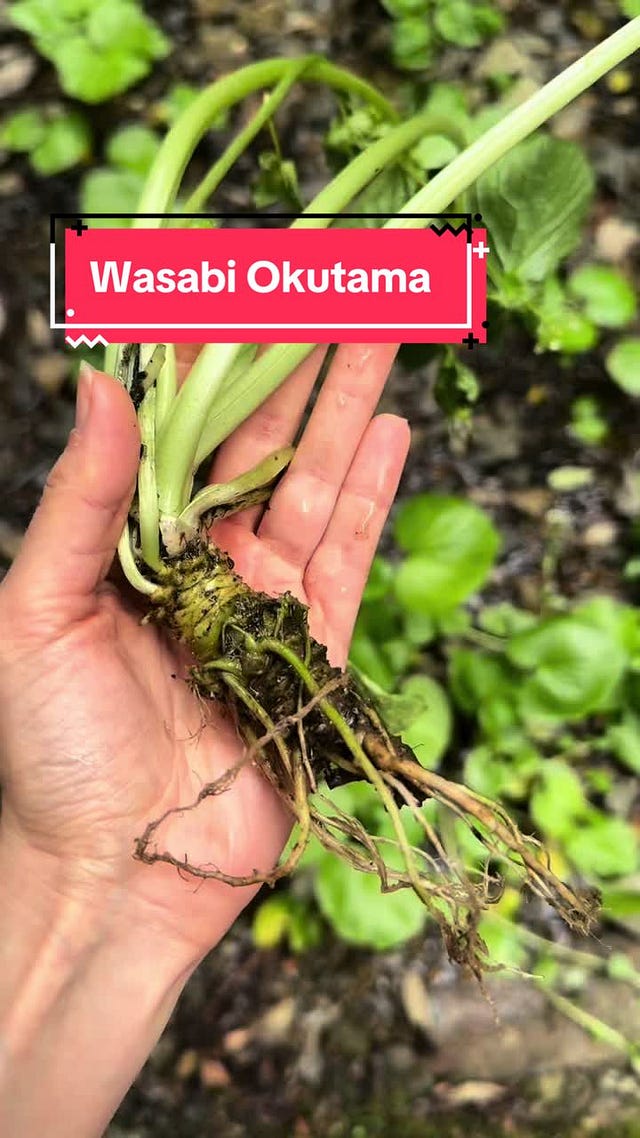

If you’re not familiar with wasabi, it’s a green root that grows under gorgeous, bright green, kiwi-like leaves. Wasabi, also known as Wasabia japonica, is a member of the Brassicaceae family alongside horseradish and mustard. If you’ve ever had a dollop of bright green wasabi as an accompaniment to your sushi before, it is likely that this was fake wasabi! This more common “wasabi” (if we want to call it that) is actually not wasabi at all but rather European horseradish dyed bright green to resemble the real stuff.*

I’ve always loved wasabi and considered it a real treat when eating it at a nice Japanese restaurant. If you ever see it being ground in front of you, just know your tastebuds are in for a treat. Real wasabi will be slightly chunky whereas fake wasabi will be perfectly smooth as it has been pureed to a paste consistency.

*To be honest, I even love the fake stuff although it does not even compare with what I’m going to share with you today. I once had a wasabi Kit-Kat years ago and have unsuccessfully tried to procure more since then.

Ideal Conditions for Wasabi

I was pleased to learn from David that this is actually the perfect time of the year to harvest wasabi because it’s not too cold and not too hot. During the cold months, the plant expends so much energy to stay alive so the growth is very slow. During the summer, the wasabi plant doesn’t love the heat so unless it is planted under big trees that provide shade, it can wither and wilt. The best growing conditions for wasabi are under deciduous trees - these have no leaves during the winter so the sun can reach the wasabi when out, and then in the summer the leaves provide shade to cool the wasabi down. The ideal tree is the hinoki tree as it can grow leaves and doesn’t mind having wet feet!

Wasabi grows in water and as you can see in the video above, ideally there is a constant flow of water hitting the plant. It is commonly planted in rows both so that if the water is limited you can push it to exact areas but also because of beautiful Japanese neatness and organization. The flow of the water is very important because wasabi gets its nutrients directly from the water and these nutrients affect the flavor. Ideally this water is around 12C.

During colder months, David doesn’t put nets on his wasabi plants as snow can actually crush them. If there’s a continuous flow of water, the wasabi plants will continue growing, just be a tad slower.

David’s Wasabi Plants

There are around 15-20 wasabi varieties, each slightly different in size, color, and growth timing. In David’s wasabi da (field), he had Mazuma (真妻) and Masamidori (正緑) varieties. He explained to me that these are smaller varieties so they pack more of a punch. The bigger the wasabi leaf and the faster it grows, the less pungent and flavorful it will be.

Bigger leaves = less flavor = take less time to grow

While his plants take 2 years to produce a root suitable to eat, new mass market wasabi varieties only take a year. While these have bigger leaves, they pack less of a punch. With these faster varieties and new hydroponic technology across many countries, it is very difficult for smaller-scale, traditional wasabi farms to remain in business in Japan. David explained that even though he had four patches in Okutama, he does not sell any of his wasabi as there simply isn’t enough. He only uses these to teach visitors about the beautiful rhizome and as gifts for his friends. It’s a true art.

It’s a tough job! He put me to work loosening up the ground for new plantations using his kazusa blade and my back is feeling it today. The smaller version of this tool is called a tekusa, a hand kazusa and is used for planting.

Another fact I learned was that both wasabi leaves and wasabi flower sprouts are edible! The leaves tasted of wasabi without any heat and with an earthier, mushroom-like flavor. Prior to the flower blooming, you can actually pick the soft shoots and pickle them. I had never even seen a wasabi flower before this past Sunday but how sweet are these :’)

The Taste Test

I’ve had the pleasure of trying real wasabi before at omakase restaurants and while it was freshly ground in front of me, it was then always placed in between the rice and the fish in nigiri. Tasting it fresh immediately post grind and then 2-3 minutes later, opened up to a vast array of flavors I did not know wasabi could possess.

First up, plain wasabi on its own. To prepare the wasabi, we picked a few and then cleaned them off using a deer antler (!). Once cleaned, David grated it right in front of me in forceful circular motions, told me to put it on my finger and just plop it into my mouth. I happily acquiesced and my goodness - it tasted herby with a warming sensation but really not too pungent. The taste lingered but the spice dissipated quickly.

Then he grated some more and told me to wait… and then wait some more… 3 minutes later, I was allowed to taste it plain again. WOW - I was not expecting that spice level in this second bite. It was hot hot hot but still had flavor so it didn’t overwhelm my palate. Whereas the first taste test was a soft and warming kind of spicy, this second one packed more of a punch and hit me right in the nostrils. I loved it.

Both delicious, but entirely different.

We then went on to have this fresh wasabi on creamy, raw scallops and sweet fish sticks. The wasabi paired perfectly with these lighter flavors but never took away from their individual tastes which surprised me if I’m being honest.

What is wasabi spice like?

There’s a French saying, la moutarde me monte au nez, mustard goes up to my nose. Since both mustard and wasabi are part of the same family, the Brassicaceae family, it’s normal that wasabi gives off this exact same sensation! Chili heat comes from capsaicin and hits the tongue, Brassicaceae heat comes from allyl isothiocyanate and goes straight to your nez, your nose!

Final Thoughts…

This experience was a real treat. I really hope to taste this level of high grade wasabi once again in my lifetime. Thank you so much for taking the time to teach me all about wasabi David!

If you have the chance to travel to Japan and would like to go on this adventure, you can find David’s details here.

If you’d like to receive my Tokyo city guide next week, please make sure to subscribe below!

Stay tuned for all of my restaurant, activity, shopping recs and more! I’ll be sure to include some basic phrases and travel information as well since many of you have been messaging me about these specifics.

living vicariously through you

Fascinating

What a great experience